The history of the Dallas Police Department (DPD) is a direct reflection of the city’s own evolution. The transition to an organized law enforcement service became noticeable in 1914. That year, the new Municipal Building opened. Officers already had standard uniforms and approved 2nd issue badges, which were used until 1952. Police operations were constantly modernizing: by the 1930s, the first dispatch consoles appeared on duty, significantly boosting patrol efficiency. But the real test of resilience came in the 1960s. During this time, female officers began to join the force. November 1963 plunged the DPD into the epicenter of a global drama. This is a story of formation, risk, and remembrance for those who gave their lives in service. Among them are Officers J.D. Tippit and Ray Hawkins. More at dallas-yes.

The Formation of the Dallas Police Department

If you were to pinpoint the year the Dallas police truly “suited up” as we know them, it would undoubtedly be 1914. This date symbolizes not just another staff appointment, but a fundamental shift in the city’s law enforcement philosophy. It was then that the new Municipal Building was inaugurated—a true modernist marvel for the city at the time. The construction of such a facility meant that the city government had finally decided to centralize its functions, and the Police Department (DPD) received a new, permanent, and, most importantly, official headquarters.

Testament to this new era is the famous photograph of officers and department members gathered on the wide steps of the new city hall. This was a significant public act, as it demonstrated to Dallas residents that the police were now a stable, numerous, and, no less importantly, unified force. Notably, it was during this period that the 2nd issue badges were introduced, becoming a true hallmark of the Dallas police. They were an element of identity that remained almost unchanged until 1952.

But professionalization required more than just a new building and a nice badge. As the city began to grow rapidly, effective patrolling and communication became critically important. For example, by 1938, officer John C. Wilson wasn’t just walking the streets with a whistle; he was working at a dispatch console. This was a significant technological breakthrough, as direct radio communication between headquarters and patrol cars allowed for a rapid response to crimes. Police crews could now coordinate their actions, sharply increasing their ability to catch offenders and maintain order. Compared to the previous system—which was essentially manual information relay—it’s clear the DPD was beginning to master the latest advancements of its time.

Cold War Chronicles

The 1940s and 1950s were a time of rapid growth, industrialization, and, of course, Cold War challenges for Dallas, all of which inevitably impacted police work. Whereas the DPD had previously focused on internal structuring, its main task now became modernization to meet the needs of an expanding city.

It was during this time that innovation ceased to be a nice bonus and became a necessity. The implementation of an improved radio system, which not only connected headquarters to patrols but also enabled ‘car-to-car’ communication, was a true revolution. This allowed patrol crews to coordinate pursuits or cordons without constantly checking in with a dispatcher. This direct link significantly reduced incident response times.

This new era of modernization also demanded updated symbols. In 1952, the Department said goodbye to the old 2nd issue badges that had served officers faithfully since 1914.

Alongside technological advancements, the Dallas police also began adapting to social changes. Although the full integration of women and minorities into the police ranks would come later, the 1950s saw the first bricks being laid for a more inclusive department. As crime took on new forms and urban life became more complex, the DPD was forced to not only patrol the streets but also to build relationships with the community.

Dallas Police at the Epicenter of Tragedy

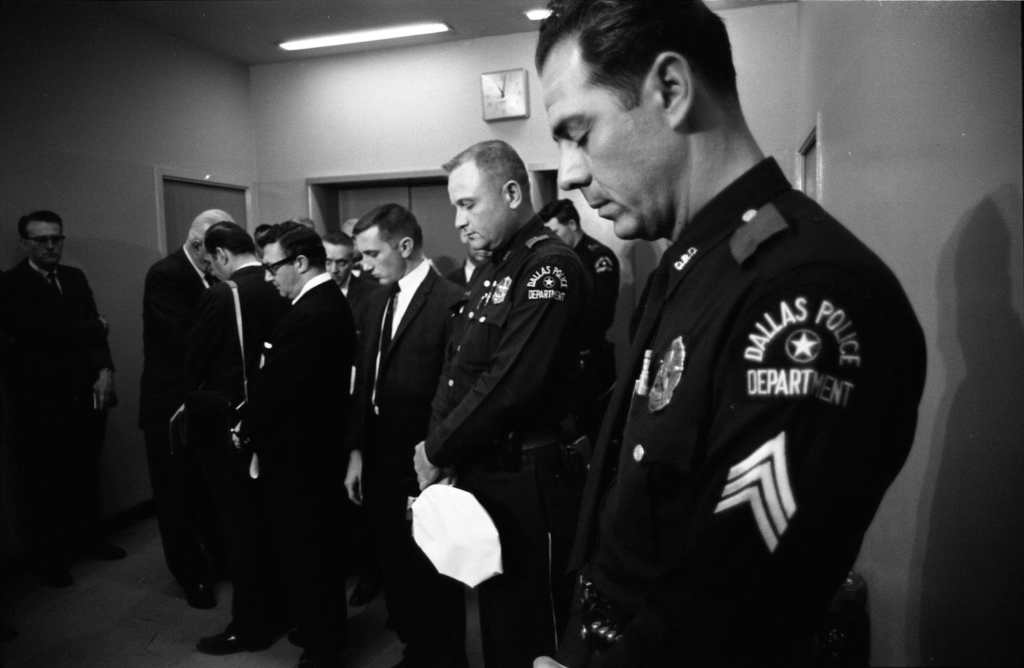

November 1963 became a true test for the Dallas Police Department, one that would define its reputation for decades to come. On that fateful day when President John F. Kennedy was assassinated, the DPD found itself not just at the center of American media attention, but in the focus of the entire world. It was a shock that paralyzed the city, and the responsibility for maintaining order and conducting the investigation fell squarely on the police.

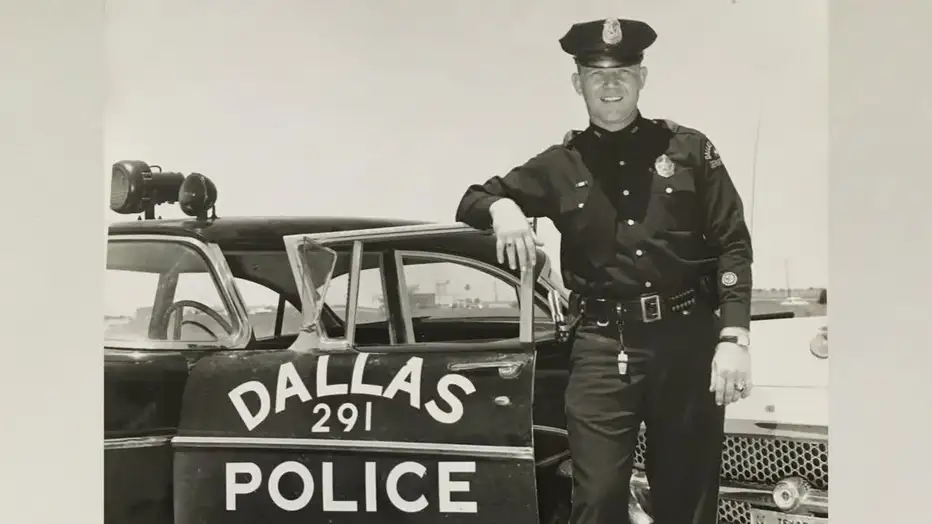

What happened next is a tragic and inseparable part of DPD’s history. Officer J.D. Tippit was killed while on patrol. He was murdered by Lee Harvey Oswald, and his death underscored the dangers of police work, becoming a personal tragedy against the backdrop of a national catastrophe. Tippit was, after all, performing routine duty when he encountered the assassin.

Events unfolded rapidly, and the DPD headquarters at the Municipal Building transformed into a de facto command center. The Homicide & Robbery Bureau, led by Captain Fritz, was operating there, and it was where Oswald was taken after his arrest. One can only imagine the chaos and tension that filled the narrow third-floor hallways. Officers had to guard Oswald, fending off journalists and preserving evidence, even as cameras and microphones pressed in from all sides. Every step they took, every word they spoke, immediately became part of world history.

When Oswald was about to be transferred, the police, despite attempting to ensure security, were caught off guard. His murder by Jack Ruby, right in the basement of the police station, was a second shocking blow.

The Faces of the Dallas Police Department

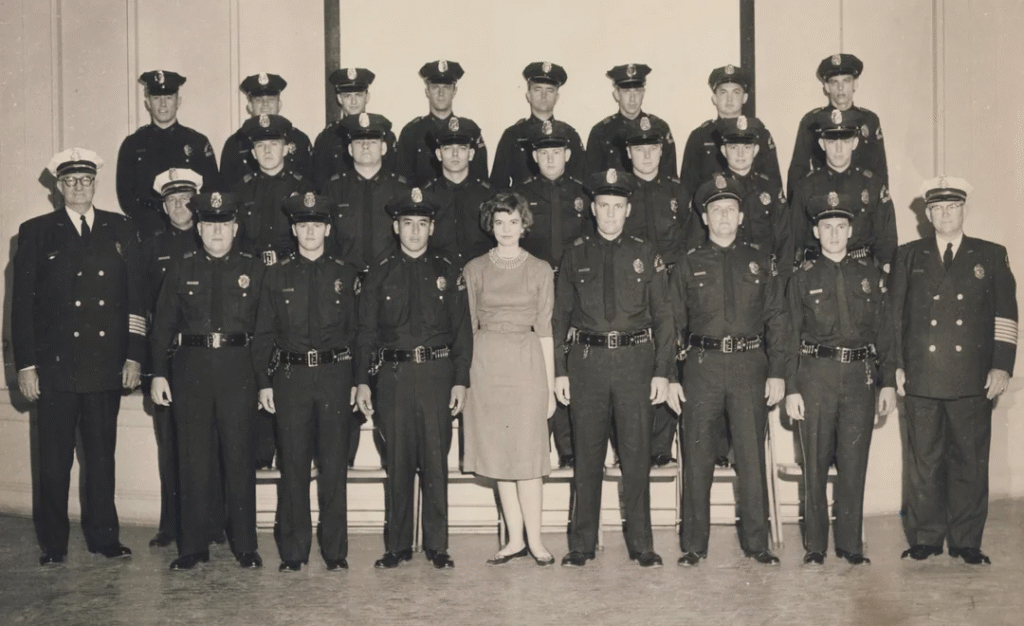

Looking at the mid-century, one of the most significant social changes was the gradual inclusion of women into the DPD ranks. Although the first female officers appeared much earlier, a 1963 photograph of a young woman graduating from the police academy speaks volumes about this growing integration.

However, the price of this service was often extremely high. The names of officers who died in the line of duty are ingrained in the department’s consciousness as a reminder of the constant risk. We have already mentioned J.D. Tippit, who became a victim of the national tragedy, but unfortunately, there are many such stories.

Corporal Ray Hawkins holds a special place among them. His story is an example of quiet but profound service. Ray Hawkins worked for the DPD for several years, but his name is forever associated with the courage he showed during a dramatic incident. In the 1950s, while Hawkins was on duty, he confronted a dangerous criminal, which led to his tragic death. His death became a painful reminder that danger doesn’t only lurk during high-profile events. Every time he is remembered, it confirms that heroism is often found in daily, routine work that, in an instant, can demand the ultimate sacrifice.

The modern DPD meticulously upholds these traditions of remembrance, holding full-scale honors and commemorating its fallen colleagues decades later. All of these stages—from the unified badges of 1914 to the crisis response of 1963—have shaped the DPD’s current culture, which balances tradition, innovation, and a deep respect for those who paid the highest price.

Sources: