The history of Dallas City Hall is a unique, century-plus chronicle of city government, marked by radical architectural transformations. Until 1872, city officials were forced to constantly rent space, a testament to the uncertainty of early self-governance. But the real intrigue unfolded in 1910: the old castle-like city hall was sold to tycoon Adolphus Busch. He unceremoniously demolished it to build the lavish Adolphus Hotel, transforming a seat of power into a haven for the elite. More at dallas-yes.

The next building, the Municipal Building, went down in history less for its architecture and more for a national tragedy. On November 24, 1963, its basement was the scene of the fatal shot when Jack Ruby killed Lee Harvey Oswald. This moment gave the municipal structure a grim historical significance. The final, and perhaps boldest, chapter in this story was written by I.M. Pei, who designed the modern Dallas City Hall, which opened in 1978.

A City Hall Without Permanent Walls

From 1856 to 1872, during the first years of Dallas’s city government, aldermen were forced to literally ‘wander,’ holding meetings in temporarily rented spaces because no permanent workplace existed. A shift finally came in 1872 when a committee was formed, succeeding in constructing the first, albeit modest, permanent two-story building at Main and Akard streets. Municipal offices were located on the second floor, but even this solution was short-lived: by 1881, the city government had moved again, this time to Commerce and Lamar streets.

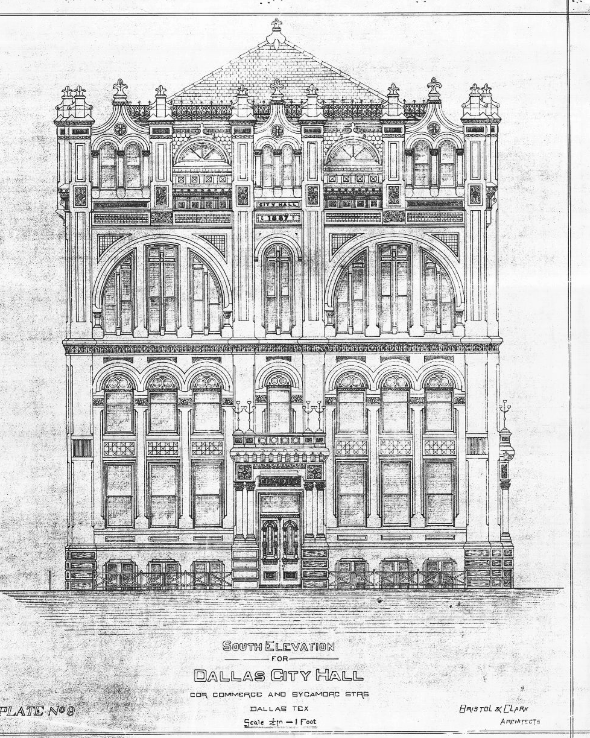

A true architectural achievement, though temporary, was the castle-like stone building in the Renaissance Revival style, which was inaugurated on June 29, 1889, at Commerce and Akard Street. This city hall served the city until June 22, 1910, when an event occurred that changed downtown Dallas: the land was sold to baron Adolphus Busch. He quickly demolished the old building to erect his luxurious Adolphus Hotel on its site. For the city, this wasn’t just a real estate sale, but another ‘exile’ of its government: while a new location was sought, municipal offices again settled into temporary quarters, this time on Commerce Street between St. Paul and Harwood.

Construction Conflicts and a National Tragedy

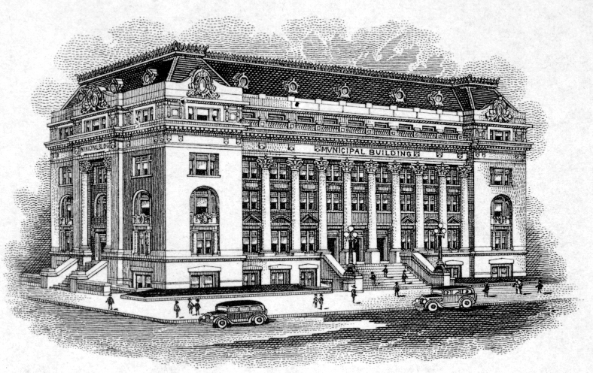

The next municipal seat—the Municipal Building—was designed by C.D. Hill in the classic Beaux-Arts style and opened its doors on October 17, 1914, at 106 S. Harwood. Its construction immediately turned into a drama: the city financed the project with funds from the sale of land to Busch and from lots purchased from Eliza Trice, Otto Lang, and the Sweeney family ($23,500.00). In the spring of 1913, the Fred A. Jones Building Company began work, but by November of that same year, it had unexpectedly gone bankrupt. As a result, the Board of Commissioners had to pass a resolution to take over the materials and finish the project themselves.

This building became historic not so much for its architecture, but for being the backdrop to a national tragedy. On November 24, 1963, the world watched as Jack Ruby shot Lee Harvey Oswald in the building’s basement during a prisoner transfer. That fatal shot forever made the building a part of the nation’s criminal history. Although it featured WPA murals in the 1930s (works by Jerry Bywaters), which were later destroyed, it continued to serve the city until 1978. Even after the main administration moved to the new city hall, this complex remained home to key city services for a long time: the Dallas Police Department, Dallas Fire Department, and Municipal Court Services.

The I.M. Pei Project

The need for a modern administrative center became evident, and on June 24, 1964, the Dallas City Council established a committee to address it. In February 1965, a new site at the intersection of Akard, Canton, Ervay, and Marilla streets was recommended. To realize the ambitious project, they enlisted world-renowned architect I.M. Pei, famous for his work on the John F. Kennedy Library and the Louvre Pyramid.

Pei developed a radical design: a building that slants at a 33-degree angle, which he intended to symbolize the openness and accessibility of city government. It was a bold departure from traditional architecture.

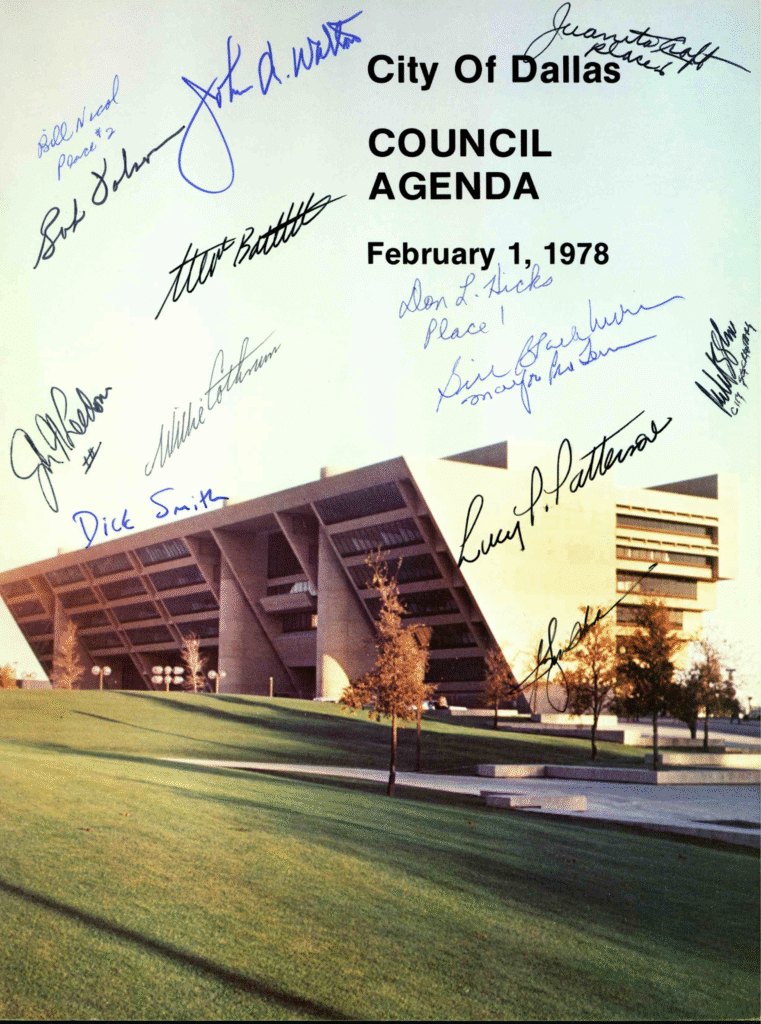

The tension surrounding the project was aptly summarized by Wes Wise at the groundbreaking: ‘It’s time to sing or get away from the piano,’ underscoring the city’s final resolve. Construction, which began on June 26, 1972, under contractor Robert E. McKee, was not without controversy. The initial $42.2 million budget swelled to over $70 million, sparking criticism over cost overruns and aesthetic debates about the avant-garde style. The work was completed in phases: acceptance of the garage areas (November 1974), the Park Plaza (May 1976), and the building itself (December 1977).

The new Dallas City Hall was much more than just an administrative building—it became the city’s symbolic answer to its national shame. In 1964, the mayor at the time initiated the ‘Goals for Dallas’ program, a direct response to the city’s tarnished reputation after the 1963 assassination of President Kennedy, which had earned Dallas the nickname ‘City of Hate.’ I.M. Pei was tasked with designing a building that would inspire confidence in the government and reflect civic pride.

The radical idea of an inverted pyramid was not just an aesthetic choice, but also a functional one: public areas required less space than the offices. By cantilevering the upper floors outward, Pei not only increased the workspace but also created a protective canopy over the plaza and entrances from the blistering Texas sun. For the construction, the architect insisted on using ‘buff-colored concrete,’ a hue reminiscent of the local soil. Interestingly, Pei drew inspiration not only from modernism but also from a less expected source: a municipal courthouse in India had a similar sloped structure.

The Modern Dallas City Hall

The modern Dallas City Hall, on its 11.8-acre site, was formally opened and dedicated on March 12, 1978. Its total area is approximately one million square feet, including two underground parking levels for 1,426 cars. The first City Council meeting was held in the new city hall on February 1, 1978.

I.M. Pei’s philosophy of ‘openness’ was embodied in the interior space. The building, designed for 1,400 workstations, has minimal permanent walls; instead, low partitions (5-7 feet) are used. This allows employees and visitors to access natural light and exterior views from almost any point. The heart of the interior is the Great Court on the second floor—a massive public area 250 feet long, with a vaulted ceiling soaring approximately 100 feet high. The City Council Chamber spans three stories and features theater-style seating for 250 people. In front of the building lies the Park Plaza, a space bordered by Young, Ervay, Marilla, and Akard streets. The plaza includes a 180-foot diameter Reflecting Pool, a variable-height fountain, and three distinctive 84-foot flagpoles. Thus, I.M. Pei’s Dallas City Hall became not just an administrative center, but an architectural symbol of modern, accessible government.

Sources: