The 1918 flu pandemic was the deadliest in history, claiming approximately 50 million lives worldwide. Initially, when the first cases of the virus appeared in the spring, it didn’t seem particularly dangerous. However, just six months later, a far more lethal strain began to be diagnosed, causing rapid fatalities among the infected. People were dying within days or even hours of their first symptoms. Read more at dallas-yes.

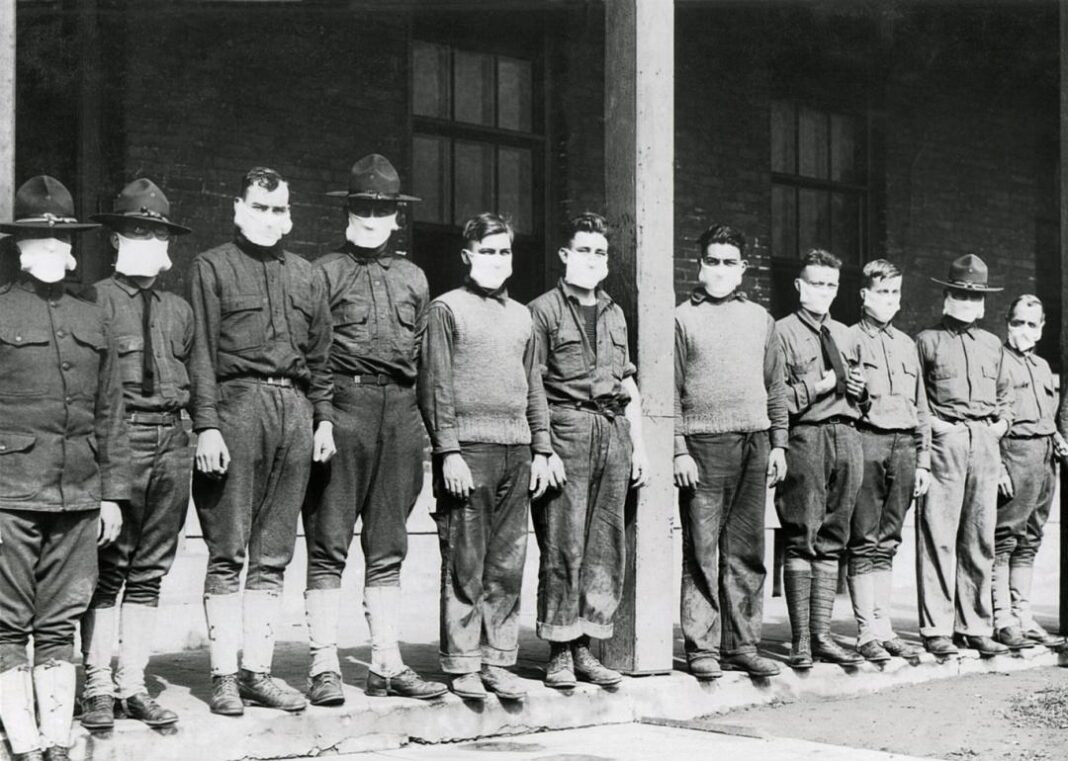

Since there was no vaccine for this flu at the time, authorities attempted to curb its spread through public safety measures. People were urged to avoid large gatherings and wear masks, but unfortunately, even these efforts couldn’t stop the virus from spreading.

First Cases of Spanish Flu in Dallas

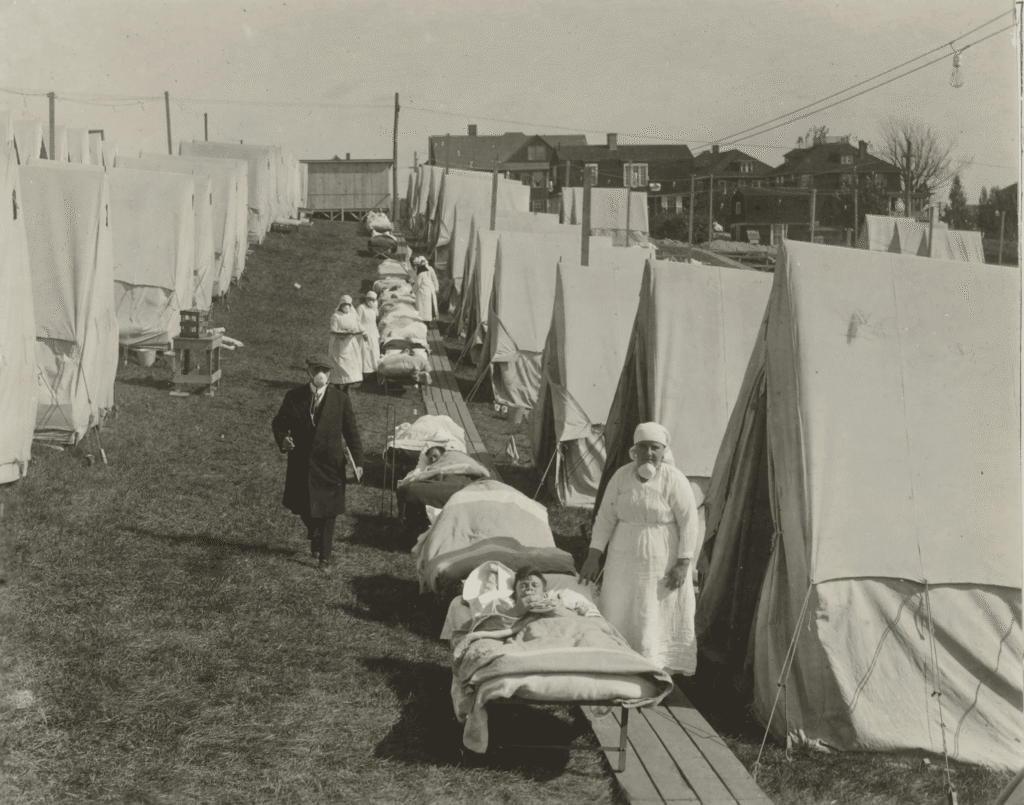

On September 24, 1918, the national press was just beginning to cover the growing flu epidemic on the East Coast of the United States. Dallas Health Officer Dr. A. W. Carns warned local residents that the disease would inevitably reach their city. At that time, Camp Logan, near Houston, had already reported around 700 cases among military personnel. Due to the immense number of sick individuals and poor conditions in local hospitals, temporary hospitals even had to be established there. Furthermore, isolated cases were already being recorded in other Texas cities, such as at Camp Bowie in Fort Worth.

Despite the grim news, Carns didn’t consider the new virus particularly dangerous and compared it to a common cold. He advised city residents to follow basic preventative measures: get more fresh air, avoid crowds, and seek medical attention promptly at the first signs of symptoms. Meanwhile, The Dallas Morning News published an article stating that the threat of an epidemic was exaggerated.

However, just a few days later, Dallas recorded its first five civilian flu cases. As the disease spread, medical professionals implemented restrictions in local military camps to protect at least the soldiers from the flu. At Camp John Dick aviation concentration camp, all newly arrived cadets were quarantined, and at Camp Bowie, soldiers were prohibited from gathering in theaters, billiard halls, and even dances.

By September 27, the number of officially confirmed Spanish flu cases in Dallas had risen to 15. But because there wasn’t a strict requirement to report symptoms, local doctors estimated that the actual number of infected individuals was four times higher.

The Liberty Loan Parade and the City’s First Fatality

The indifference and incompetence of Dallas’s health officer led to the Liberty Loan parade taking place in the city center on September 28. Approximately 5,000 civilians and 2,500 military personnel participated. At the event, city residents supported the Fourth Liberty Loan campaign. Activists sang the song “For Your Boy and My Boy” and marched through one of the city’s largest neighborhoods. However, the consequences of the Liberty Loan parade proved to be dire.

By October 3, Dallas had already registered 119 cases of Spanish flu. Again, doctors assumed that the real number of infected people was significantly higher. The first citizen to die from the disease was 15-year-old Pierpont Bolderson. On September 30, the boy passed away at St. Paul’s Hospital.

Following these events, local hospitals began isolating patients, and the Dallas Baby Camp, a charitable children’s hospital, decided to close its doors to regular visitors. The Spanish flu epidemic also affected 20 Red Cross volunteers working at Union Terminal railway station.

Despite the rapidly worsening situation, Dr. A. W. Carns still refrained from implementing strict quarantine measures and simply recommended avoiding places with unsatisfactory sanitary conditions.

Quarantine Restrictions Imposed in Dallas Due to the Flu Outbreak

Since the Dallas health officer was slow to take necessary action, others concerned about the lives of Dallasites stepped in to help. George W. Simmons, director of the Southwestern Division of the Red Cross, began mobilizing volunteers and seeking resources to combat the epidemic. The Dallas County Nurses’ Registry also joined the effort, trying to recruit as many qualified nurses as possible. They appealed to female students, retirees, and private nurses. An isolation ward for the most severe cases was prepared in the basement of Parkland Hospital.

On October 9, Dallas Mayor Joseph Earl Lawther convened a meeting of the board of health. At the meeting, participants agreed that doctors must report all flu cases. Additionally, they agreed to start public education efforts. However, opinions were divided regarding stricter measures. Some doctors insisted on the immediate closure of all public places, while others considered this decision premature.

On October 10, the mayor issued an order to close all theaters and entertainment venues, but schools remained open. At the same time, Carns instructed public transport to be disinfected and limited the number of passengers. On October 12, despite the health board’s position, Joseph Earl Lawther independently ordered the closure of all schools and churches. By then, there were already 2,719 confirmed cases of Spanish flu in the city.

In addition to quarantine measures, the city authorities organized a large-scale sanitation campaign. Boy Scouts were enlisted to clean the streets, and women were urged to clean their homes.

During the flu outbreak, vulnerable populations were the most affected. Due to racial prejudice, the city’s Black population had almost no access to medical care. A special nurse was assigned to care for them. A similar situation existed among residents of Mexican descent.

Scale of the Spanish Flu Outbreak in Dallas

It’s incredibly difficult to determine the full extent of the Spanish flu’s impact on Dallas. Although doctors were supposed to report cases from September 27, the relevant law didn’t take effect until October 12. This brief time gap meant many cases went undocumented and, therefore, are forever lost to history.

Another problem is the lack of detailed official statistics for our contemporaries. Unlike other cities that meticulously analyzed the course of the epidemic in their 1918 reports, Dallas authorities gave it minimal attention. For unknown reasons, greater emphasis was placed on smallpox, malaria, and food quality issues. The only accurate figure available is the total number of deaths in Dallas from influenza and pneumonia between May 1918 and May 1919, which stands at 813 cases.

Some data can be found in the local press, although it’s also quite contradictory. On December 13, The Dallas Morning News reported 286 deaths from influenza or pneumonia per 100,000 residents since October 1, but just a few days later, it published a completely different figure – 250 deaths per 100,000 residents.

But even considering the significant discrepancies in the data, Dallas experienced the epidemic more mildly than most American cities. The city suffered less than other southern U.S. cities like New Orleans or Birmingham.

- https://www.influenzaarchive.org/cities/city-dallas.html?fbclid=IwAR1s4E5x7HvQmSmW93H8QoCSNWxTC1L-wf4jaYwnaSxg8B3jTalMFt8CPWU#

- https://oakcliff.advocatemag.com/2020/03/heres-how-dallas-managed-the-1918-flu-pandemic/

- https://stacker.com/stories/texas/dallas/how-dallas-fared-during-1918-spanish-flu-pandemic